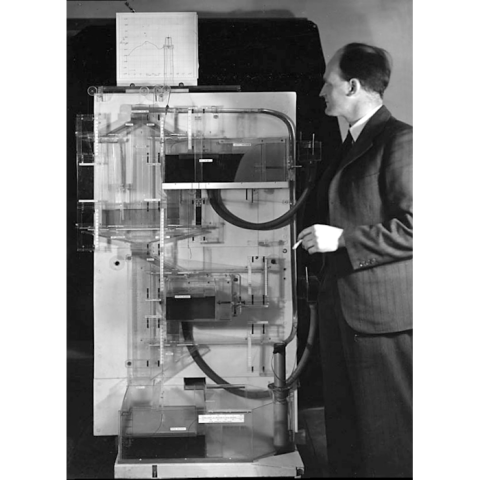

At Cambridge we are lucky enough to have a working analogue computer developed in the 1950s which represents money as flowing around the national economy. Valves can be opened or closed to represent variable effects, such as the rate of interest on savings or investment.

Professor Allan McRobie oversaw the refurbishment of the machine nearly 20 years ago, and it is now one of the few that is still in full operation. As he says; “we discussed whether it was appropriate to renovate such an important part of history, and decided that since there is an original, but non-functional, example in the Science Museum, it would make sense to bring one machine fully back to life, and also to update some working parts.”

Developed from 1949 onwards, by the New Zealand economist Bill Phillips, the machine is also known as the MONIAC (Monetary National Income Analogue Computer). It has a series of transparent plastic tanks and pipes fastened to a steel board the size of a wardrobe. Each tank represents a sector of the UK national economy and the flow of money around the economy is illustrated by coloured water, kept clear in our example.

Professor McRobie says “ Water representing all the money in the economy is pumped to the top of the machine from a large tank at the base, from where it cascades to other tanks representing the various ways in which a country could spend its money.”

For example, there are flows representing government spending and private investment which combine with the flow representing the money spent on the high street as consumption. The combined flow then cascades further down the machine, with an anabranch heading off to represent spending on imports and one joining with the proceeds of export sales. They all return to the main tank at the base of the machine to represent the all important national income, from where the water can head up and around again.

The flow of water is automatically controlled through a series of floats, counterweights, electrical probes, and fine cable wires which lift slotted graphs which move sliders across waterfalls, opening or constricting them in pre-defined ways according to what other flows are doing.

The original water pump, which was salvaged from a Lancaster Bomber, still provides the power to lift water to the top of the machine, however other parts have had to be updated to comply with modern safety standards. “It was rather shocking to see live, 240 volt probes were inserted into the water to monitor levels. We’ve stepped that down to 20 volts for safety,” he adds.

Our machine in the Faculty of Economics resides in the Meade Room, and for the past few years has been stored, and non-working. However, Professor McRobie gave the machine another overhaul before demonstrating it this term to assembled academics and students, assisted by Emily Evans, a PhD student in the Faculty of History researching the history of economic thought. “For three years, as a result of the pandemic, the machine wasn’t used or drained as we went into a sudden lockdown. As a result, we’ve had to clean out all of the pipes. We’ve got through a lot of pipe cleaner to get it working again,” said Professor McRobie.

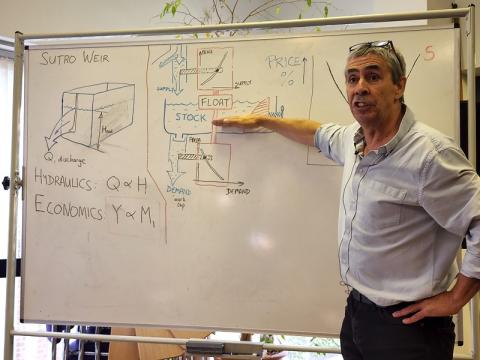

McRobie explained the machine’s history, and that of its creator, to assembled students, at one of two demonstrations this Easter term. “William Phillips MBE was a fascinating character. He was born in New Zealand in 1914, and hunted crocodiles in Australia. He qualified as an engineer then moved to the UK, aged 22. He flew with the RAF, spent three years in a POW camp, and after the war studied sociology at the London School of Economics. Facing up to a third-class degree, he developed an interest in Keynesian theory, created hydraulic macroeconomics, demonstrating the machine, before becoming a Professor at the LSE.”

His best-known contribution to economics is the Phillips curve, which he first described in 1958. Phillips noticed a historically inverse relationship between unemployment and the rate of change of money wage rates in the United Kingdom. It was thinking about the inevitable short-comings in his hydraulic model that led Phillips to his curve.

If you are in London, and wish to see a static, conserved, model of the Phillips Machine, the MONIAC used by the LSE is on display in the Science Museum in the museum's mathematics galleries.